-

Route 1: Capital Access and Deployment

Transforming Lives and Communities in Greater Boston

For years, a dark, hulking warehouse on Pleasant Street in Brockton, Massachusetts, and its overgrown parking lot served as a magnet for illicit activity. Drugs. Gangs. Violence. Graffiti.

Located in one of the state’s original 11 “Gateway Cities,” Brockton has been designated as a struggling urban center facing tough social and economic challenges. The Pleasant Street parcel had long housed a national chain supermarket before becoming a warehouse. After the latter was abandoned, the building fell into disrepair. Brockton police were among the most frequent visitors to the blighted property.

Today, that parcel has been completely transformed by local entrepreneurs and community leaders with financing from The Kresge Foundation, Boston Community Capital and several other investors. Locally based Vicente’s Supermarket opened a new location there in the summer of 2015, offering the city’s large Cape Verdean population healthy, traditional foods and more than 100 jobs. Rounding out the $20 million complex is Brockton Neighborhood Health Center’s gleaming new primary care facility, which employs a full-time nutritionist to shop with patients and demonstrate healthy cooking in the center’s test kitchen.

Supporting Conscientious Lenders

Nutritionist Mary Lynch conducts a cooking class at Brockton Neighborhood Health Center. The Pleasant Street complex exemplifies the social investment Kresge is making in cities across New England through its support of community-oriented lenders like Boston Community Capital. Another $3 million program-related investment loan from Kresge in 2016 is paving the way for Boston Community Capital and its partner, MassDevelopment, to continue this work not only in Brockton – where 18 percent of residents live in poverty and the average annual household income is below $50,000 – but also in 10 other small-to-medium-size Massachusetts cities hit hard by the loss of manufacturing jobs.

“For us to have a healthy society, a healthy culture and a healthy economy, we need to invest in all of our communities including those that have been traditionally underserved,” says Boston Community Capital CEO Elyse Cherry. “Low-income communities and populations are vital contributors to the health and wealth of our communities; when we strengthen opportunities in these communities, the entire regional economy benefits.”

Traditionally, under-resourced communities like Brockton have struggled to attract the kind of capital investment they need to catalyze long-term economic growth. Kresge believes every community contains creativity, human and economic capital and inherent worth – a philosophy that helped pave the way to a 2015 commitment by its Board of Trustees to allocate $350 million toward social investments in traditionally underserved cities and neighborhoods. One of the first outputs of that commitment in 2016 was a $30 million loan initiative for community development finance institutions and qualifying development finance authorities working in sectors that align with the foundation’s programmatic goals.

Brockton Neighborhood Health Center interpreter Judith Varela guides residents through Vicente's Supermarket, which is located in the same complex. More than 60 organizations applied for Kresge Community Finance loans through the initiative, which provided 10-year financing at below-market interest rates. Additionally, each recipient received a small grant equal to 5 percent of the total loan amount.

“Solving complex social problems requires that we change behaviors, markets and policy using grants and investments,” says Kimberlee Cornett, managing director of Kresge’s Social Investment Practice. “We’re trying to use a full suite of capital tools – grants, debt, equity, guarantees and deposits – and identify investments using those tools that are supportive of those goals that we’re trying to achieve.”

Boston Community Capital received its loan through Kresge Community Finance. Cornett says criteria for being awarded a loan included close alignment with Kresge’s programmatic strategies, strong organizational finances, a track record that shows community impact and the probability of repayment.

“Boston Community Capital is a highly creative, well-led, well-capitalized organization,” Cornett explains. “Kresge had a prior investment with BCC that was fully repaid, so we are pleased to be in their roster of investors again.”

Unconventional Financing

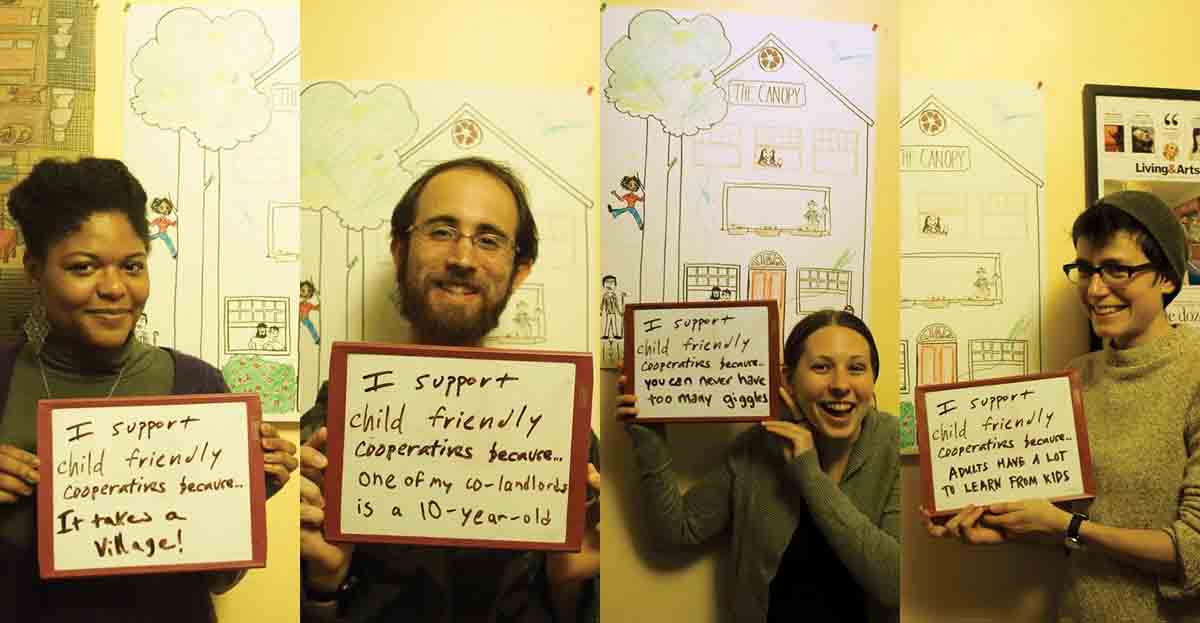

Another Boston-area recipient of a Kresge Community Finance loan was the Cooperative Fund of New England. It will use a $1 million loan to continue financing projects that are owned and directed by stakeholders – workers and community members, for instance – rather than outside investors.

According to U.S. Department of Commerce Minority Business Development Agency data, black and Latino residents face large disparities in access to financial capital. Minority-owned businesses are more likely to be denied credit, are less likely to apply for loans for fear of having their applications denied and pay higher interest rates than white counterparts when loans are granted.

After the Affordable Care Act was passed, Kresge created its Healthy Futures Fund to fill gaps in care. The $200 million fund was crucial in developing the Brockton Neighborhood Health Center. Cooperatives like those financed by the Cooperative Fund of New England are also a solution when outside investors refuse to lend in neighborhoods where returns are often smaller, slower or both.

Kresge has long supported community development finance institutions (CDFIs) like the Cooperative Fund of New England. These private financial institutions are solely dedicated to delivering responsible, affordable lending to help low-wealth and other disadvantaged people and communities become part of the economic mainstream. In lending situations where other banks may see risk, CDFIs see both financial opportunity and social reward.

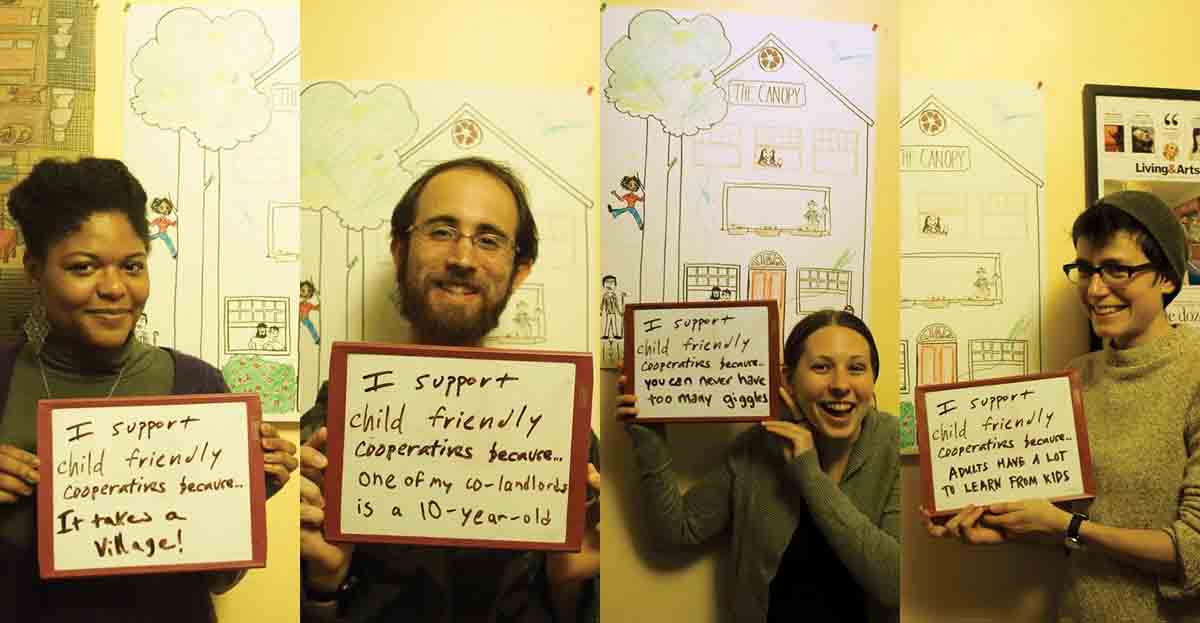

“Co-ops are nontraditional business models that are owned by a lot of different people in a democratic manner. A lot of conventional lenders don’t really know how to finance cooperatives within their regulatory environment,” says Micha Josephy, program manager at the Cooperative Fund of New England.

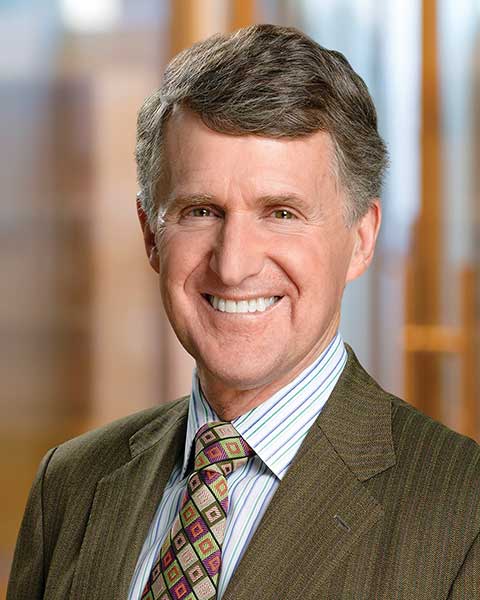

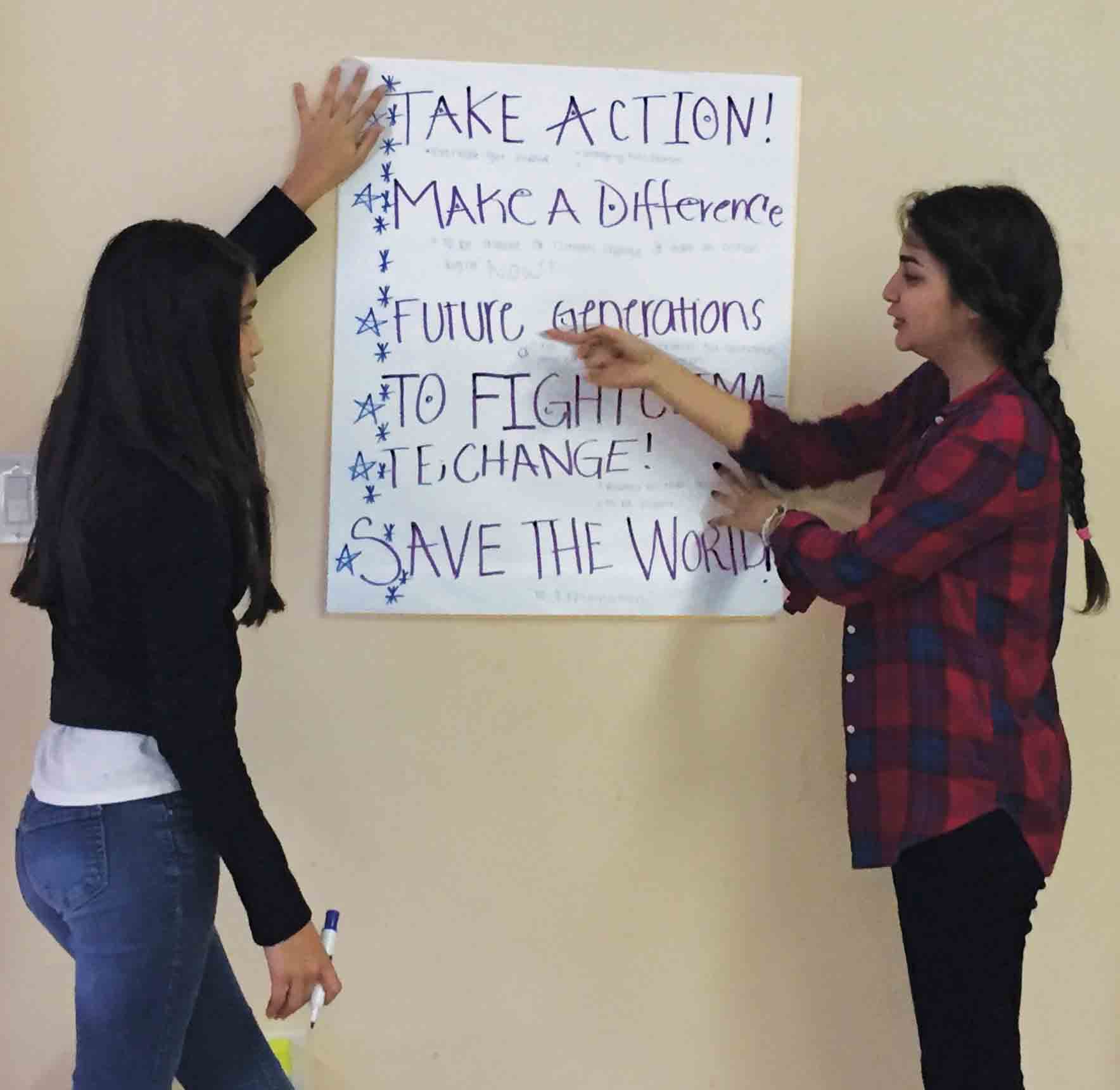

Boston's Dorchester neighborhood is home to new cooperative living spaces and the Dorchester Food Co-op, an initiative to build a community- and worker-owned grocery store that will make healthy food accessible. In the expensive, quickly gentrifying Boston housing market, the Cooperative Fund partnered with Boston Community Cooperatives in 2007 to form Seedpod, a 12-bedroom, cooperative living space in the city’s Dorchester neighborhood. Besides enjoying more affordable, group equity-based housing, Seedpod’s residents – 12 adults, two children and two cats – enjoy a community-focused living environment. Residents share food and meals, have a collective chore system and meet weekly to make consensus decisions about house operations.

The Cooperative Fund of New England is currently partnering with Boston Community Cooperatives to close on a second cooperative housing community, The Canopy, also in Dorchester. It will focus on accommodating adults with children.

“This is a very exciting step for us, and we are excited about the wide range of groups and individuals who are interested in being part of BCC’s next house,” says Jennie Msall, who has lived at Seedpod for seven years. “We believe cooperative housing can play a substantial role in stabilizing neighborhoods, conserving resources and creating social spaces in an increasingly distracted, isolating world.”

Fostering Collaboration

Kresge believes it isn’t enough simply to invest money in creating opportunity in cities. For capital to be absorbed and put to its best use, research has shown it takes healthy cooperation across private, public and nonprofit sectors.

Jethro Charlestin restocks produce at Vicente's Supermarket's Pleasant Street location. It's a favorite among local residents of Cape Verdean descent. “Capital is like water,” says Robin Hacke, a former senior fellow at The Kresge Foundation who researched and incubated a capital absorption practice to improve the ability of cities to attract and leverage capital for investment in public projects. “If you want it to soak into the ground instead of just running off, you have to know what’s in the soil – what kinds of collaborations are present and how to foster them.”

This was the rationale behind the Working Cities Challenge, a landmark initiative of the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston that was funded in part by Kresge. After studying and working with the city of Springfield, Massachusetts, from 2008 to 2011, the Boston Fed identified 25 U.S. cities that had struggled economically after the decline of manufacturing and industrial businesses. Among the 10 post-industrial cities that had experienced revitalization, the common thread was not a city’s capital investment, geographic position or industry mix. Rather, it was leaders’ commitment to collaboration across sectors for the long-term success of all.

So, the Boston Fed did something no reserve bank had ever done. With financial support from Kresge, it put out a call in 2013 for collaborative and ambitious economic development strategies to improve the lives of low-income people in small and midsize Massachusetts cities bruised by the departure of industry and manufacturing.

The Canopy cooperative housing community is accommodating adults with children in Dorchester. These “working cities” are collectively home to 1.5 million Bay Staters – more than twice the population of Boston. Winning proposals were selected for their pledge to lead collaboratively across public, private and nonprofit sectors; desire to engage community members; use of evidence to track progress toward a shared goal; and commitment to work to improve the lives of low-income residents by changing systems.

“We’re hoping that this effort is an inspiration and a model for other reserve banks to partner in this way with philanthropic and state and community efforts,” says Prabal Chakrabarti, senior vice president and community affairs officer at Working Cities Challenge.

Behind a $1.5 million grant from Kresge in 2016, the Working Cities Challenge is now receiving a second round of submissions in Massachusetts and has launched inaugural competitions in Connecticut and Rhode Island. Connecticut has one of the largest wealth disparities in the country, with many formerly thriving manufacturing cities now suffering economically. Meanwhile, Chakrabarti sees the state’s small size as being Rhode Island’s greatest opportunity.

Flexible capital is helping stabilize housing to improve the lives of people in cities bruised by the departure of industry and manufacturing. “(In a small state like Rhode Island), you can get state policy more closely aligned with what’s happening in the cities. There are only two workforce boards in Rhode Island, and only one community college,” he says. “They happen to have an energetic governor who’s been doing a lot to bring in some companies and businesses to the state.

"Linking into that energy is important.”

Opening the Gates

From Providence to Brockton to Boston and throughout New England, Kresge’s Social Investment Practice is opening the flow of capital to parts of the region hit hard by economic distress.

Entrepreneurs, previously denied access to financing for their small businesses, are seeing their dreams realized. Families on the verge of foreclosure are being stabilized. Long-blighted properties are seeing new life and promise. Leaders from multiple sectors are meeting face-to-face, in some cases for the first time, to collaborate creatively for the betterment of their cities.

“Anyone who thinks this is simple has never tried,” says Boston Community Capital’s Cherry. “It requires flexible capital, understanding the community and bringing various stakeholders together – exactly the kind of systems change that Kresge believes in.”

Share this program!

While the Upcoming Challenges are Great, We are Greater

By Elaine D. RosenChair, Board of Trustees

I recently and quite by accident came upon a note I had sent to our foundation staff at the end of 2016. Following a successful fourth-quarter board meeting, I wrote, in part:

Please do remember that while the upcoming challenges are great, we are greater. Our work is strong and our talent ... well ... that simply blows the mind. In the year ahead, we will navigate several new realities carefully and wisely – led by Sebastian Kresge’s mission and our values as an institution.

The discovery of the note took my breath away. When I wrote it, the uncertainties of December had not yet given full view to the pace and extent of a new governing and policy-making environment.

What centers me while considering the impact of changes since then is remembering that philanthropy by its nature is steady – and steadfast.

Since 1924, The Kresge Foundation has been carrying out our founder Sebastian Spering Kresge’s mandate to promote human progress through grant making. And since 2006, we have developed a strategic philanthropy that engages an array of tools to expand opportunities in America’s cities.

During these 93 years, our government leaders and prevailing ideologies have come and gone. The political climate has bended and shifted. The economy has experienced peaks and troughs – and after those troubling troughs, always a healthy rebound.

Through it all, The Kresge Foundation has remained focused and a force for change to promote the greater good.

That focus is more important than ever when government actions create chaos and new policies seem to threaten the most vulnerable among us. In response, we are taking stock, adjusting our course, playing with the hand we are dealt.

For those reasons, the Kresge Board of Trustees authorized for 2017 an increase in the foundation’s capacity to engage with issues and movements precipitated by the new political and policy environment by making selected one-time grants as well as long-term investments.

But we will not be shaken from that for which we stand.

We will lead with our values, driven by the credo of our founder to leave the world a better place than we found it.

We will persevere. Certainly, we all realize that philanthropy is incapable of fully replacing government supports – the 2014 U.S. federal budget was nearly four times the assets of all U.S. philanthropies combined. That said, we have the will and wherewithal to respond when ill-advised government cutbacks result in human fallout.

We will stand for equity and justice. The implications of rolling back social programs and supports are profound, especially toward people in cities who do not seek a handout, but rather, a hand up.

We will concentrate our work in cities. More than 80 percent of the U.S. population lives in and around cities where strong, bold, visionary leadership on the ground is yielding positive outcomes from coast to coast.

We will defend science: Fifty years of data show that climate change is as real as the urgency to address it.

We will stand for facts and truth. Period.

We will continue to believe in the strength and resolve of American talent and the power of citizen-leaders in communities urban, rural and in-between.

We will remain nimble, prepared to act as circumstances require, our minds focused, our tools at the ready.

In Appreciation

On behalf of all our trustees, I note with regret that two people I so dearly admire will depart the Kresge board in 2017 after serving their 16-year terms. It is hard to consider our board without their presence.

Irene Hirano Inouye, who preceded me as board chair, has been a personal mentor and role model to most of us on the Kresge board. Among Irene’s countless talents and contributions, her knowledge has brought Kresge to the forefront of good governance and her grace and leadership have raised our board discourse to a superior level.

I got to know Lee Bollinger while successfully co-leading the search for our new president in 2006 (successful in that it resulted in Rip Rapson’s appointment). Lee is an inspirational thought leader who has helped open my eyes to the breadth of the foundation’s philanthropic potential.

We are indebted to Irene and Lee. They will be missed beyond measure.